Request a Johne’s test on your next herd test if you have not already done so!

It is that time in the season that is the most opportune moment to perform a whole herd screen Johne’s test to find positive cows. Removing these cows now saves on the costs of wintering them and reduces the chances of infection in the biggest risk period during calving.

Cows infected with Johne’s generally do not perform well over the challenge of transition and calving, and it is often enough to tip them over the edge and they deteriorate clinically. In one case study performed by LIC, a third of cows testing high positive had died on farm during the calving period. Cows testing positive are more likely to leave the herd by dying on farm than going to the works, compared with cows testing negative.

Any cows which test positive, should be retested with a blood test to confirm the identity of that cow. In a season where reproductive results have been strong, there may be more flexibility to remove cows from the herd which test positive. It may well aid culling decisions, looking at SCC, udder conformation and mobility, if Johne’s status is known also. It is also becoming common practice for buyers to request a Johnes test before purchasing cows.

LIC Johne’s Dashboard Development

LIC are currently developing a dashboard, via MINDA, to better display and manage Johne’s positive cows within the herd, based on historic and current Johne’s results on farm. It is currently in a trial period at the moment, but from what we have seen it is looking to be useful tool to help visualise the extent of a JD problem on each farm. Particularly interesting is showing which cohorts have been most at risk to infection, and benchmarking compared with national average.

It is still in a prototype phase, but may well prove to be an important tool in seasons to come. Watch this space.

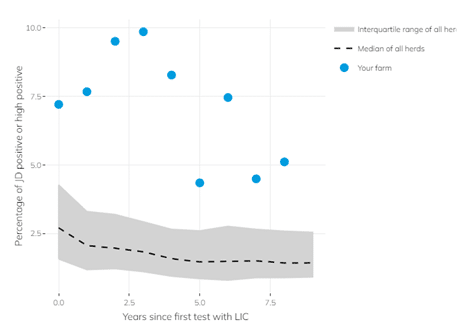

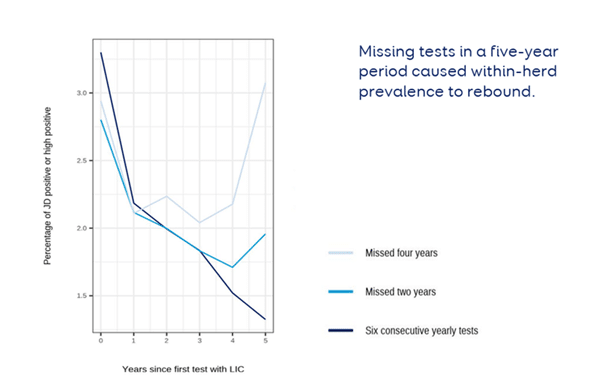

Below is a extract, taken from LIC’s website, about the importance of testing and showing how missing a year’s testing can cause Johne’s prevalence to resurge.

Prevalence of JD positive and high positive results in herds testing with LIC 2013-2023

* Note this is industry median data so may not predict what may happen on individual farms.

Key takeouts from this graph:

- Farms that had six consecutive annual tests made the most progress in terms of reducing prevalence (3.3% to 1.3% over the five years since their first test).

- Herds that missed two annual tests within this same period tended to have a rebound in prevalence (from their initial starting point, a median of 2.80% to their lowest median prevalence of 1.71% after three years to 1.96% after five years).

- Median prevalence rebounded in herds that missed four annual tests to levels close to those identified when testing started (2.94% at year 0 to 2.04% after three years to 3.07% after five years).

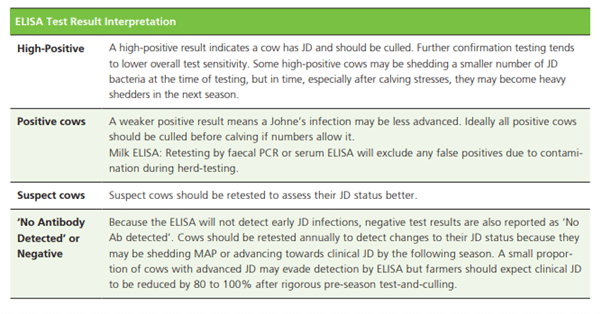

Interpreting the results

The Johne’s ELISA is a very specific test – which means if a cow tests positive we know she is positive. However, sensitivity is poor, which means if a cows tests negative, it does not necessarily mean she isn’t infected with Johne’s disease. In any case, culling positive cows is the best way to make big leaps in managing Johne’s.

Below is a summary table explaining what each individual result means.

Testing and culling cows is of course only part of the solution. Management of the disease on farm will help mitigate spread. Below are some good resources available discussing management options, and further information on testing.

Resources

Dairy NZ Johne’s Disease Management – https://www.dairynz.co.nz/media/gyibqbzc/animal-johnes-disease-management.pdf

Dairy NZ Johne’s Laboratory Testing – https://www.dairynz.co.nz/media/brtkqlv2/johnes_disease_laboratory_testing_a4_booklet_web_april_2018.pdf

LIC Johne’s Herd Test – https://www.lic.co.nz/products-and-services/animal-health-and-dna-testing/johnes-disease-testing/